Arctic Art and Transformations

Ascendant Artists offer Alaska Native Masterworks Show in Sisters

Each Spring, as has happened for millenniums, masses of filtering feeding baleen whales in the Pacific Ocean migrate North, making the thousands of miles journey to the krill and plankton rich Alaskan waters. They’ll swim another thousand miles along the Southeastern Archipelago and Southern Coast of Alaska before reaching and passing through the Aleutian Island chain. There, they’ll turn north once more and swim yet another thousand miles up the Bering Sea before reaching the most nutrient abundant waters of all, the Arctic Ocean.

Along the way, the great behemoths swim by countless seals, otters, sea lions, coastal brown bears, walrus, bald eagles, and polar bear, along with schools of herring and salmon underneath and innumerable flocks of waterfowl overhead. On shore, the sudden return of the whales arouses an innate longing within the traditional peoples—they’re irresistibly compelled to commence the hunting seasons for all these things yet again.

The Alaskan Native Peoples still do this, after millenniums, although their equipment is mostly non-traditional now. Another change to their lifestyle is that certain parts of these animals are utilized as materials and inspiration for the making of artwork for the Outside world, artwork that respectfully honors these very things.

The taking of bowhead whales is limited to the Inupiat people who live along the coast. Other Alaska Native Peoples who live along the coast may harvest other marine mammals. There has long been a tradition of trading the animal parts among the Peoples, so any Alaska Natives may acquire and produce the materials necessary for art making.

Don Johnston, Aleut, moved to Anchorage from Ketchikan, Alaska 35 years ago to work construction but suffered a somewhat fortuitous back injury. While recovering, he met the highly acclaimed Inupiaq baleen basket weaver James Omnik Sr. James taught him the art and Don eventually became so skilled that some are now heralding him as perhaps the finest baleen basket weaver ever.

Baleen baskets are literally woven with the filtering plates found inside the mouth of krill eating whales. Baleen has strength and flexibility comparable to fiberglass, so attempting to weave a small, intricate basket of this rigidity demands strength and fine motor dexterity at the same time. Typically, an elegantly carved walrus ivory handle or finial sits atop the basket’s lid.

Don’s contemporary perspectives on the traditional art form not only explore the possibilities of what baleen baskets can be but led him to capture the 2017 Best of Show Award at the renowned and juried Native American art show—the Heard Museum Indian Fair and Market in Phoenix, AZ. Seldom does an artist from Alaska gain entrance to this annual event; to win Best of Show is unprecedented.

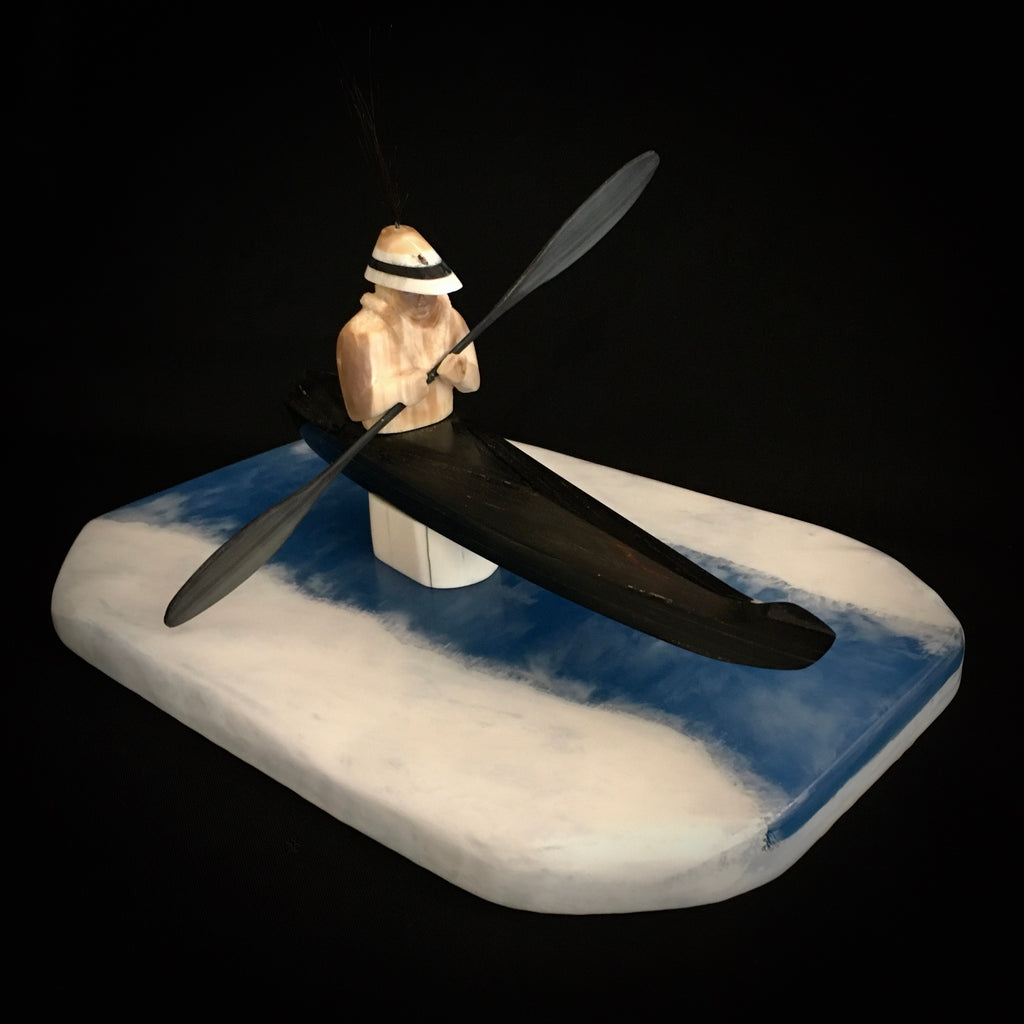

Mark Tetpon, Inupiat, is a wood-walrus ivory-bone master carver who is virtually unknown outside of Alaska and the Pacific Northwest. He has done numerous shows in Anchorage and Seattle, where his pieces are quickly acquired, thus secreting away knowledge of his works and awareness about his prodigious talent.

Mark’s pieces depict sea mammals or birds as they are understood within the spiritual realms of his people. A sculptured polar bear or walrus might be drumming; an honoring mask that depicts a loon or seal’s body will be surrounded by a dozen smaller sculptures paying homage to the life of The People.

Mark’s father, John, from the traditional village of Shaktoolik along the Bering Sea Coast near Nome, mentored him in the ways of the Inupiaq people and during Mark’s early artistic endeavors. John still assists Mark with some of his pieces.

Bronze and ceramic sculptor Terresa White, Yu’pik Eskimo, is being lauded as one of the blossoming talents in the Native American art world. Her fresh perspectives on the ancient Yup’ik belief of transformation garnered a Best of Sculpture Award in 2018 at the Santa Fe Indian Market, the other apex event for Native American art venues.

Transformation concerns the traditional Yup’ik belief that a human can at least spiritually, if not also physically, become an animal—and vice versa—if proper behaviors are maintained. Thus, humans and the animals reside in a type of metaphysical brother/sisterhood coexistence. Terresa's works honor the interconnection of all beings, often focusing on the defining moments of the metamorphosis.

In-person art and exhibition in Sisters April 26-28

Artist Reception on Friday from 4 to 7 pm, demonstrations on Saturday.

All events will take place at Raven Makes Gallery at 182 E. Hood Avenue.